Utilisateur:Ayack/Brouillon/Radar Dnestr

| Pays d'origine | URSS, Russie |

|---|---|

| Mise en opération | 1963 (Dnestr-M) |

| Quantité produite | 15 |

| Type |

surveillance de l'espace (Dnestr) alerte avancée (Dnestr-M, Dnepr, Dnepr-M) |

| Fréquence | 154–162 Hertz (VHF)[1] |

| Largeur de faisceau | 0.5°(N-S), 10°(E-W)[1] |

| Longueur d'impulsion | 0.8 ms long[2] |

| Portée | 3 000 km[3] 1 900 km for targets with an area of 1 m2[2][4] |

| Diamètre | Each array is 244 m long, 20 m high and 12 m wide[1] |

| Azimut | 30°[5], 30 per transmitter giving 120 in total[2][4] |

| Élévation | 5° to 35°[4] |

| Précision | ± 1 km range, 10 min azimuth, 50 min elevation, 5 m/s range rate [4] |

| Puissance crête |

peak power of 1 % MW per transmitter[2][4] Radiating power 200 kW [4] Consumed power 2100 kW[4] |

| Autres noms |

NATO: Hen House[6] GRAU: 5N15 (Dnestr), 5N15M (Dnestr-M), 5N86 (Dnepr) |

Les radars de type Dnestr (russe : Днестр) et Dnepr (russe : Днепр) (code OTAN: Hen House[note 1]) constituent la première génération de radars soviétiques de surveillance de l'espace et d’alerte avancée. Rassemblés dans un système à commande de phase, ils sont conçus pour donner l'alerte en cas d'attaque de missiles balistiques. Ce réseau était composé à l'origine de six stations radars réparties aux frontières de l'union soviétique afin de prévenir les attaques provenant de différentes directions. Il devait être remplacé par les radars Daryal, mais en raison de la dislocation de l'URSS, seul deux de ces radars furent construits. De ce fait, en 2012, trois stations fonctionnent encore mais devraient être remplacées par des radars Voronezh de troisième génération à l'horizon 2020.

Comme plusieurs autres radars d'alerte soviétiques puis russes, les radars Dnestr et Dnepr tirent leur nom de fleuves, le Dniestr et le Dniepr[note 2].

Historique

modifierTsSO-P

modifierLe radar Dnestr résulte de travaux menés à la fin des années 1950 et au début des années 1960 sur la défense contre les missiles balistiques. Parmi ces recherches, figure System A, le prototype du système de missiles antibalistiques A-35 qui fut conçu sur les bancs d'essai de Sary Shagan, en République socialiste soviétique kazakhe[7]. Sa conception fut réalisée par le bureau d'études KB-1 qui s'appuya sur le radar VHF RTN (РТН) et celui UHF Dunay-2. D'autres possibilités furent recherchées auprès de l'industrie soviétique qui proposa d'utiliser le radar VHF TsSO-P (ЦСО-П) et l'UHF TsSS-30 (ЦСС-30)[8].

Le TsSO-P (abréviation de центральная станция обнаружения – полигонная signifiant station centrale de détection – site test) fut finalement sélectionné, ainsi que le Dunay-2[8]. TsSO-P était composé d'une antenne cornet de 250 m de long et de 15 m de haut. It had an array with an open ribbed structure and used 200 millisecond pulses. Hardware methods were designed for signal processing as the intended M-4 computer could not run the radar. It was built at area 8 in Sary Shagan and was located at 46° 00′ 04,65″ N, 73° 38′ 52,11″ E. It first detected an object on 17 September 1961[8].

TsSO-P took part in the 1961 and 1962 Operation K tests at Sary Shagan to examine the effects of nuclear explosions on missile defence hardware[8].

Dnestr

modifier

TsSO-P was effective at satellite tracking and was chosen as the radar of the Istrebitel Sputnik (IS) anti-satellite programme. This programme involved involved the construction of two sites separated in latitude to form a radar field 5 000 kilomètres ( Unité « » inconnue du modèle {{Conversion}}.) long and 3 000 kilomètres ( Unité « » inconnue du modèle {{Conversion}}.) high. The two sites chosen were at the village of Mishelevka near Irkoutsk in Sibérie, which was called OS-1, and at Cape Gulshad on Lac Balkhach near Sary Shagan, which was called OS-2. Each site received four Dnestr radar systems in a fan arrangement[9],[8],[10].[11][11][12]

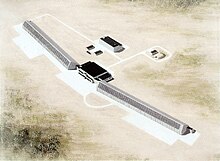

A Dnestr radar was composed of two TsSO-P radar wings joined together by a two story building containing a joint computer system and command post. Each radar wing covered a 30 degree sector with a 0.5 degree scanning beam. The elevation scanning pattern was a 'spade' with a width of 20 degrees. The radar systems were arranged to create a fan shaped barrier. Of the four radars, called cells (РЛЯ roughly radio location cell), two faced to the west and two faced to the east. All scanned between +10 degrees and +90 degrees in elevation[8].

Construction at the two sites started between 1962 and 1963 with improvements in the TsSO-P test model being fed back into the deployed units. They gained an M-4 2-M computer with semi-conducteurs, although the rest of the radar used Tube électroniques. The radar systems were completed in late 1966 with the fourth Dnestr at Balkhash being used for testing[8]. In 1968 the Dnipropetrovsk Spoutnik target satellite, DS-P1-Yu, was used to test the ability of the system[12],[13].

The Dnestr radars were accepted for service by the Voyska PVO in April 1967 and became part of the space surveillance network SKKP[8].[11][14]

Dnestr-M

modifierParallel with the implementation of the Dnestr space surveillance units, a modified version of the original Dnestr units, Dnestr-M radar, was being developed to act as an early warning radar to identify attacks by missile balistiques. The first two were built at Murmansk in northern Russia (Olenegorsk – RO-1) and near Riga in the then République socialiste soviétique de Lettonie (Skrunda – RO-2). They constituted the beginning of the Soviet SPRN network, the equivalent of the NATO Ballistic Missile Early Warning System.[11][8],[15]

The first Dnestr-M at Olenegorsk was completed by 1968[8]. In 1970, the radars at Olenegorsk and Skrunda, and an associated command centre at Solnetchnogorsk, were accepted for service. According to Podvig (2002), it seems they were positioned to identify missile launches from NATO submarines in the Norwegian and Mer du Nords[5].

The Dnestr-M included many improvements over the previous versions such as an increase in the pulse length from 200ms to 800ms which increased the range of objects identified, more semiconductors, and many other scanning and processing changes[8].

A version of this radar was built at the Sary Shagan test site and was called TsSO-PM (ЦСО-ПМ). After this had completed tests in 1965 it was decided to upgrade nodes 1 and 2 of the two OS sites to Dnestr-M, keeping nodes 3 and 4 as Dnestr. These radars remained as space surveillance radars which scanned between +10 and +90 degrees, comparative to scanning between +10 and +30 degrees for the missile warning radars. A space surveillance network of four Dnestrs and four Dnestr-Ms, and two command posts was formally commissioned in 1971[8].

Dnepr

modifierWork to improve the radar continued. An improved array was designed which covered 60 degrees rather than 30. The first Dnepr radar was built at Balkhash as a new radar, cell 5. It entered service on 12 May 1974[2]. The second was a new early warning station at Sevastopol. New Dneprs were also built at Mishelevka and another at Skrunda, and then one at Mukachevo. The remaining radars were all converted to Dnepr with the exception of cells 3 and 4 at Balkhash and Mishelevka which remained space surveillance radars[8],[5].[11]

All current operational radars are described as Dnepr, and have been updated incrementally[2],[16].

Caractéristiques

modifierEach Dnepr array is a double sectoral antenne cornet 250 m long by 12 m wide[2]. It has two rows of slot radiators within two guide d'ondes. At each end of the two arrays, there is a set of transmitting and receiving equipment. It emits a signal covering a sector 30 degrees in azimuth and 30 degrees in elevation, with the scanning controlled by frequency. Four sets mean the radar covers 120 degrees in azimuth and 30 degrees in elevation (5 to 35 degrees)[2].

The Dnepr involved the horn antenna being reduced from 20 to 14 metres in height and the addition of a polarising filter [8]

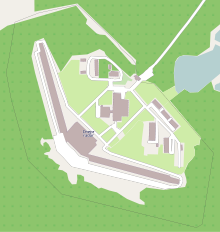

Stations radar

modifierSix stations différentes ont mis en œuvre ces radars dont trois restaient opérationnelles en 2012 (Balkhash, Mishelevka et Olenegorsk[16],[17],[2]). En 1972, le traité ABM interdit le déploiement de systèmes antimissiles balistiques ayant un but autre que la protection de Moscou. Cela entraîne différents problèmes lors de la dislocation de l'URSS en 1991, plusieurs de ces stations se retrouvant dans des pays nouvellement indépendants[18],[5],[15],[19]. La première station à fermer est Skrunda, en Lettonie. Un accord signé en 1994 entre les gouvernements russe et letton entraîne l'arrêt des deux radars en 1998 et leur démolition en 2000[20],[21],[11].

En 1992, la Russie a signé un traité avec l'Ukraine, lui permettant de continuer à utiliser les radars Dnepr de Sébastopol et Mukachevo. Les stations étaient opérées par du personnel ukrainien qui transmettait les données au quartier-général du dispositif d'alerte situé à Solnechnogorsk[22],[23]. En 2008, la Russie annonça son retrait de l'accord, la fin de transmission des données ayant lieu en 2009[24],[25],[26], l'Ukraine de son côté reconvertissant les installations afin d'effectuer de la surveillance spatiale[27],[28].

La station de Balkhash au Kazakhstan possède le dernier radar Dnepr opérationnel hors du territoire russe. Modernisé, il est opéré par le VKO, la défense aérospatiale russe[2],[29].

Les stations restantes, qui sont situées sur le territoire russe, doivent être remplacées à terme par d'autres équipées de radars Voronezh[30],[25],[17].

| Désignation | Emplacement | Coordonnées | Azimut[5] | Type | Construction | Détails |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS-1 | Station radar de Mishelevka, Oussolié-Sibirskoïé, Irkoutsk, Sibérie | 52° 52′ 39″ N, 103° 16′ 24″ E | 135 | Dnestr | 1964–1976 | Modernisé en Dnestr-M puis en Dnepr à la fin des années 1970. Opérationnel[31],[32] |

| 52° 52′ 53″ N, 103° 15′ 58″ E | 135 | Dnestr | 1964–1970 | Modernisé en Dnestr-M. Déclassé dans les années 1990. À l'abandon[32]. | ||

| 52° 52′ 59″ N, 103° 15′ 29″ E | 265 | Dnestr | 1964–1968 | Modernisé en Dnestr-M. Utilisé pour la recherche depuis 1993 – constitue désormais un radar à diffusion incohérente[1],[32] | ||

| 52° 52′ 33″ N, 103° 15′ 23″ E | 265 | Dnestr | 1964–1968 | Modernisé en Dnestr-M. Déclassé dans les années 1990. À l'abandon[32]. | ||

| 52° 52′ 29″ N, 103° 15′ 39″ E | 70, 200 | Dnepr | 1967–1972 | Modernisé en Dnepr 1976. Opérationnel[31],[32] | ||

| OS-2 | Station radar de Balkhash, Sary Shagan, Kazakhstan | 46° 36′ 27″ N, 74° 31′ 24″ E | 270 | Dnestr | 1964–1970 | Modernisé en Dnestr-M. Opérationnel en 1970. Déclassé en septembre 1995. À l'abandon[2],[5]. |

| 46° 36′ 52″ N, 74° 31′ 23″ E | 270 | Dnestr | 1964–1968 | Opérationnel en 1968. Déclassé en janvier 1984. À l'abandon[2],[33]. | ||

| 46° 37′ 31″ N, 74° 31′ 02″ E | 60 | Dnestr | 1964–1968 | Opérationnel en 1968. Déclassé en 1984. À l'abandon[2],[33]. | ||

| 46° 37′ 53″ N, 74° 30′ 45″ E | 60 | Dnestr | 1964–1968 | Opérationnel en 1968. Déclassé en septembre 1988. À l'abandon[2],[33]. | ||

| 46° 36′ 11″ N, 74° 31′ 52″ E | 180, 124 | Dnepr | 1968–1972 | Opérationnel en 1972. Modernisé en Dnepr. Opérationnel depuis 1974[33],[2],[34]. | ||

| RO-1 | Olenegorsk-1, Olenegorsk, Russie | 68° 06′ 51″ N, 33° 54′ 37″ E | 323, 293 | Dnestr-M | 1963–1968 | Opérationnel. Fonctionne avec le radar Daugava, un prototype de radar Daryal[35] |

| RO-2 | Skrunda, Lettonie | 56° 42′ 55″ N, 21° 57′ 47″ E | 323, 293 | Dnestr-M | 1963–1968 | Démoli en 1998[5] |

| 56° 42′ 30″ N, 21° 56′ 28″ E | 8, 248 | Dnepr | 1968–1976 | Démoli en 1998[5] | ||

| RO-4[36] | Station radar de Sébastopol, Crimée, Ukraine | 44° 34′ 44″ N, 33° 23′ 10″ E | 172, 230 | Dnepr | 1968–1979 | Passé sous contrôle ukrainien en 1992. Fermé en 2009. Remplacé par un radar Voronezh à Armavir. À l'abandon[25],[37],[38],[39]? |

| RO-5[36] | Station radar de Mukachevo, Ukraine | 48° 22′ 40″ N, 22° 42′ 27″ E | 196, 260 | Dnepr | 1968–1979 | Passé sous contrôle ukrainien en 1992. Fermé en 2009. Remplacé par un radar Voronezh à Armavir. À l'abandon[25],[37],[39]? |

Notes et références

modifierNotes

modifier- L'OTAN leur a attribué le nom de code « Hen House » (signifiant poulailler en anglais) en raison de leur ressemblance avec ceux-ci selon Forden[6]

- De même, le radar Voronezh a été nommé d'après la Voronej, le radar Don-2N d'après le Don et le radar Dunay d'après le Dunay (Danube).

Références

modifier- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Dnestr radar » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- « Incoherent Scatter Radar » [archive du ], East Siberian Center for the Earth's Ionosphere Research, (consulté le )

- (ru) « «Днепр» на Балхаше » [archive du ], Novosti Kosmonavtiki, (consulté le )

- (ru) « Мощные РЛС дальнего обнаружения РЛС СПРН и СККП » [archive du ], RTI Mints, undated (consulté le )

- (mul) Encyclopedia "Russia’s Arms and Technologies. The XXI Century Encyclopedia": Volume 5 — "Space weapons", Moscow, Publishing House "Arms and Technologies", (ISBN 5-93799-010-2)

- Pavel Podvig, « History and the Current Status of the Russian Early-Warning System », Science and Global Security, vol. 10, , p. 21–60 (ISSN 08929882[à vérifier : ISSN invalide], DOI 10.1080/08929880212328, lire en ligne [PDF])

- Geoffrey Forden, « Reducing a Common Danger: Improving Russia's Early-Warning System », Cato Policy Analysis No. 399, Cato Institute, (lire en ligne)

- (en) Steven Zaloga, The Kremlin's Nuclear Sword: The Rise and Fall of Russia's Strategic Nuclear Forces 1945–2000, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution Press, (ISBN 978-1588340078)

- (ru) Viktor Ivantsov, « От «Днестра» до «Днепра» » [archive du ], VKO, undated (consulté le )

- Sean O'Connor, « Russian/Soviet Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems » [archive du ], Air Power Australia, (consulté le )

- « Hen House » [archive du ], Federation of American Scientists, undated (consulté le )

- (en) Oleg Bukharin, Timur Kadyshev, Eugene Miasnikov, Pavel Podvig, Igor Sutyagin, Maxim Tarashenko et Boris Zhelezov, Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces, Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, (ISBN 0-262-16202-4)

- Yu.V. Votintsev, « Unknown Troops of the Vanished Superpower », VOYENNO-ISTORICHESKIY ZHURNAL, vol. 11, , p. 12–27 (lire en ligne [archive du ])

- « DS-P1-Yu (11F618) » [archive du ], Gunter's Space Page, (consulté le )

- Yu.V. Votintsev, « Unknown Troops of the Vanished Superpower », Voyenno-Istoricheskiy Zhurnal, vol. 9, , p. 26–38 (lire en ligne [archive du ])

- A Karpenko, « ABM AND SPACE DEFENSE », Nevsky Bastion, vol. 4, , p. 2–47 (lire en ligne [archive du ])

- (ru) Anna Potekhin, « Зелёных вам фонарей! », Красная звезда [Krasnaya Zvezda], (consulté le )

- (ru) « Модернизация радаров СПРН в Северо-Западном округе начнется в 2015 году » [archive du ], Lenta.ru, (consulté le ) Erreur de référence : Balise

<ref>incorrecte : le nom « Lenta » est défini plusieurs fois avec des contenus différents. - (ru) I Marinin, « Отечественной СПРН – 40 лет », Novosti Kosmonavtiki, (consulté le )

Le modèle {{dead link}} doit être remplacé par {{lien brisé}} selon la syntaxe suivante :

{{ lien brisé | url = http://example.com | titre = Un exemple }}(syntaxe de base)

Le paramètreurlest obligatoire,titrefacultatif.

Le modèle {{lien brisé}} est compatible avec {{lien web}} : il suffit de remplacer l’un par l’autre. - (ru) I Marinin, « Отечественной СПРН – 40 лет », Novosti Kosmonavtiki, Eastview, no 339, , p. 44–46 (ISSN 1561-1078, lire en ligne)

- (en) Ramesh Chandra, Minority: Social and Political Conflict, Delhi, India, Isha Books, (ISBN 978-81-8205-140-9)

- (en) Dzidra Hadonina, Environmental Contamination and Remediation Practices at Former and Present Military Bases, Springer, , 63–69 p. (ISBN 978-0792352471), « Environmental Situation and Remediation Plans of Military Sites in Latvia »

- Andrzej Wilk, « Russia starts to dismantle the Soviet early warning system » [archive du ], Centre for Eastern Studies, (consulté le )

- (ru) Ilya Kramnik, « Арифметика СПРН: минус два "Днепра", плюс один "Воронеж" » [archive du ], RIA Novosti, (consulté le )

- (en) Pavel Baev, The Politics of Modern Security in Russia, Ashgate, , 69–88 p. (ISBN 978-0-7546-7408-5), « Neither Reform nor Modernisation: the Armed Forces Under and After Putin's Command »

- « Russia to stop using Ukrainian radars » [archive du ], RIA Novosti, (consulté le )

- Pavel Podvig, « Armavir radar fills the gap » [archive du ], Russian strategic nuclear forces, (consulté le )

- « Ukrainian radars withdrawn from operation in Russia's interests to undergo technical maintenance » [archive du ], Kyiv Post, (consulté le )

- « Source: Ukraine radar to be used to protect German satellites » [archive du ], Kyiv Post, (consulté le )

- (en) Anel Davletgalieva et Ivan Konovalov, « CITIZENS OF KAZAKHSTAN WERE HEAPED UP WITH DEBRIS OF THE USSR », Defence & Security, Eastview, no 9, (lire en ligne)

- « Russia Turns on New Missile Warning Radar » [archive du ], RIA Novosti, (consulté le )

- Pavel Podvig, « Daryal-U radar in Mishelevka demolished » [archive du ], Russian strategic nuclear forces, (consulté le )

- Michael Holm, « 46th independent Radio-Technical Unit » [archive du ], Soviet Armed Forces 1945–1991, (consulté le )

- Michael Holm, « 49th independent Radio-Technical Unit » [archive du ], Soviet Armed Forces 1945–1991, (consulté le )

- (ru) « Вручение знамени 16601 » [archive du ] [vidéo], Zvezda News, (consulté le )

- (ru) SityShooter, « РЛС "Днестр" – "Днепр-М" (actually is Daugava left) » [archive du ] [photograph], (consulté le )

-

(ru) « Всевидящий глаз России », Novosti Kosmonavtiki, Eastview, no 5, , p. 52–53 (lire en ligne)

- « Russia Won't Rent Ukrainian Radar »(Archive.org • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • Que faire ?), Kommersant, (consulté le )

- Oleksa Haiworonski, « "Dniepr" radiolocation unit at Cape Chersones » [archive du ] [photograph], Panoramio, (consulté le )

- Pavel Podvig, « Russia pulls out of an early-warning arrangement with Ukraine » [archive du ], Russian strategic nuclear forces, (consulté le )

Voir aussi

modifierLiens externes

modifier{{Soviet Radar}} [[Category:Russian Space Forces]] [[Category:Russian and Soviet military radars]] [[Category:Radar networks]] [[it:Dnestr (radar)]] [[ru:Днестр-М]]