Utilisateur:Thib Phil/Tactiques d'infanterie

Cette page est un espace de travail

XIXème siècle

modifierGuerres européennes et guerre de Sécession

modifierGuerres coloniales

modifier

Des « nations » qui ne furent point de grandes puissances mondiales ont utilisé, dans les guerres locales, d'autres tactiques d'infanterie ignorées de l' « art de la guerre » « classique ».

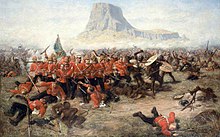

En Afrique du Sud, les impis (régiments) du peuple zoulou constituèrent de redoutables « machines de guerre » grâce à leur tactique des « cornes du taureau ». Il s'agissait d'une formation de quatre groupes de combat - deux au centre, un à gauche et un autre sur la droite - qui, enveloppant l'unité ennemie, s'en rapprochaient au plus près pour le détruire au corps à corps à la pointe de leurs sagaies ou iklwas. Les guerriers zoulous, attaquant par surprise, ont souvent ainsi débordé leurs ennemis, même beaucoup mieux armés et équipés, comme l'armée britannique lors de la Bataille d'Isandlwana.

The Sudanese fought their enemies by using a handful of riflemen to lure enemy riflemen into the range of concealed Sudanese spearmen. In New Zealand the Māori hid in fortified bunkers or pā that could withstand strikes from even some of the most powerful weapons of the 19th century before luring opposing forces into an ambush.

Unconventional infantry tactics often put a conventional enemy at a disadvantage. During the Second Boer War, the Boers used guerrilla tactics to fight the conventional British Army. Boer marksmen would often pick off British soldiers from hundreds of yards away. These constant sniper attacks forced the British infantry to begin wearing khaki uniforms instead of their traditional red. The Boers were much more mobile than the British infantry and thus could usually choose where a battle would take place. These unconventional tactics forced the British to adopt some unorthodox tactics of their own.

L'infanterie au combat dans les conflits de la première moitié du XXème siècle

modifierLa Première Guerre mondiale et la « guerre des tranchées »

modifier

Because of the increasing lethality of more modern weapons, such as artillery and machine guns, infantry tactics shifted to trench warfare. Massed infantry charges were now essentially suicidal, and the Western Front ground to a standstill.

A common tactic used during the earlier stages of trench warfare was to shell an enemy trench line, at which point friendly infantry would leave the safety of their trenches, advance across no man's land, and seize the enemy trenches. However, this tactic of "preliminary bombardment" was largely unsuccessful. The nature of no man's land (filled with barbed wire and other obstructions) was one factor. For a unit to get to an enemy trench line, it had to cross this area, secure the enemy position, then face counterattack by opposing reserves. It also depended on the ability of friendly artillery to suppress enemy infantry and artillery, which was frequently limited by "bombproofs" (bunkers), revetments, poor ammunition, or simply inaccurate fire.

An improvement was the creeping barrage in which artillery fire is laid immediately in front of advancing infantry to clear any enemy in their way. This played an important part in later battles such as the Battle of Arras (1917), of which Vimy Ridge was a part. The tactic required close coordination in an era before widespread use of radio, and when laying telephone wire under fire was extremely hazardous. In response, the Germans devised the elastic defence and used infiltration tactics in which shock troops quietly infiltrated the enemy's forward trenches, without the heavy bombardment that gave advance warning of an imminent attack. The Allies introduced the tank to overcome the deadlock of static positions but mechanical unreliability prevented them from doing so.

The Germans used specially-trained Stormtroopers to great effect in 1918, during Operation Michael, breaching the Allied trench lines and allowing supporting infantry to pour through a wide breach in the front lines. Even though most of the German forces were on foot, they were soon threatening Paris. Only timely and stiff resistance, the use of reserves, and German logistical and manpower problems prevented disaster. After this spring offensive, the Allies counterattacked with tank support, and eventually forced the Germans to retreat.

Seconde Guerre mondiale : tactiques de l'infanterie mécanisée

modifier

Since trench warfare had been rendered obsolete by the tank, new infantry tactics were devised. More than ever, battles consisted of infantry working together with tanks, aircraft, artillery, (see combined arms). One example of this is how infantry would be sent ahead of tanks to search for anti-tank teams, while tanks would provide cover for the infantry. Portable radios allowed field commanders to communicate with their HQs, allowing new orders to be relayed instantly.

Another major difference from any other previous conflict was the means of transportation; no longer did soldiers have to walk (or ride a horse) from location to location. The prevalence of motor transport, however, has been overstated; Germany used more horses for transport in WWII than in WWI, and British troops as late as June 1944 were still not fully motorized. Although there were trucks in World War I, their mobility could never be fully exploited because of the trench warfare stalemate, as well as the terribly torn up terrain at the front and the ineffectiveness of vehicles at the time. During World War II, infantry could be moved from one location to another using half-tracks, trucks, and even aircraft, which left them better rested and able to fight once they reached their objective; this also influenced speed of deployment and casualties.[1] A new type of infantry, the paratrooper, was deployed as well. These lightly armed soldiers would parachute behind enemy lines, hoping to catch the enemy off-guard. They were first used by the Germans to seize key bridges in the Netherlands, and prevented their destruction long enough for additional forces to arrive. They required prompt support from regulars, however; First British Airborne was decimated at Arnhem after being left essentially cut off.

To counter the tank threat, WWII infantry initially had few options other than the so-called "Molotov cocktail" (first used by Chinese troops against Japanese tanks around Shanghai in 1937[2]) and anti-tank rifle. Neither was particularly effective, especially if armor was accompanied by supporting infantry. These, and later anti-tank mines, some of which could be magnetically attached to the tank, required the user to get closer than was prudent. Later developments, such as the Bazooka, PIAT, and Panzerfaust, allowed a more effective attack against armor from a distance. Thus, especially in the ruined urban zones, tanks were forced to enter accompanied by squads of infantry.

Marines became prominent during the Pacific War. These soldiers were capable of amphibious warfare on a scale not previously known. As Naval Infantry, both Japanese and American Marines enjoyed the support of naval craft such as battleships, cruisers, and the newly-developed aircraft carriers. As with conventional infantry, the Marines used radios to communicate with their supporting elements. They could call in sea and air bombardment very quickly.

Époque contemporaine

modifier

The Korean War was the first major conflict following World War II. New devices, including smaller radios and the helicopter were also introduced. Parachute drops, which tended to scatter a large number of men over the battlefield, were replaced by airmobile operations using helicopters to deliver men in a precise manner. Helicopters also provided fire support in many cases, and could be rushed to deliver precision strikes on the enemy. Thus, infantry were free to range far beyond the conventional fixed artillery positions. They could even operate behind enemy lines, and later be extracted by air. This led to the concept of vertical envelopment (originally conceived for airborne), in which the enemy is not flanked to the left or right, but rather from above. The widespread availability of helicopters following WWII allowed the emergence of an air mobility tactics such as aerial envelopment.

In recent years peacekeeping operations in support of humanitarian relief efforts have become particularly important.

Guerre de jungle

modifierJungle warfare was heavily shaped by the experiences of all the major powers in the Southeast Asian theater of operations during the Second World War.

Jungle terrain tended to break up and isolate units. It tended to fragment the battle. It called for greater independence and leadership among junior leaders, and all the major powers increased the level of training and experience level required for junior officers and NCOs.

But fights in which squad or platoon leaders found themselves fighting on their own also called for more firepower.

All the combatants, therefore, found ways to increase both the firepower of individual squads and platoons. The intent was to ensure that they could fight on their own … which often proved to be the case.

Japan, as one example, increased the number of heavy weapons in each squad. The "strengthened" squad used from 1942 onwards was normally 15 men. The Japanese squad contained one squad automatic weapon (a machinegun fed from a magazine and light enough to be carried by one gunner and an assistant ammunition bearer). The squad's TO&E also included a grenade launcher team armed with what historians often mistakenly call a "knee mortar". This was in fact a light mortar of 50mm that threw high explosive, illumination and smoke rounds out to as much as 400 meters. Set on the ground and fired with arm outstretched, the operator varied the range by adjusting the height of the firing pin within the barrel (allowing the mortar to be fired through small holes in the jungle canopy). A designated sniper was also part of the team, as was a grenadier with a rifle-grenade launcher. The balance of the squad carried bolt-action rifles. The result was that each squad was now a self-sufficient combat unit. Each squad had an automatic weapons capability. In a defensive role, the machinegun could be set to create a “beaten zone” of bullets through which no enemy could advance and survive. In an attack, it could throw out a hail of bullets to keep the opponent’s head down while friendly troops advanced. The light mortar gave the squad leader an indirect "hip-pocket artillery" capability. It could fire high-explosive and fragmentation rounds to flush enemy out of dugouts and hides. It could fire smoke to conceal an advance, or illumination rounds to light up any enemy target at night. The sniper gave the squad leader a long-range point-target-killing capability. Four squads composed a platoon. There was no headquarters section, only the platoon leader and the platoon sergeant. In effect, the platoon could fight as four independent, self-contained battle units (a concept very similar to the US Ranger “chalks.”)

The British Army did extensive fighting in the jungles and rubber plantations of Malaya during the Emergency, and in Borneo against Indonesia during the Confrontation. As a result of these experiences, the British increased the close-range firepower of their individual riflemen by replacing the pre-World War II bolt-action Lee-Enfield with lighter, automatic weapons like the American M-2 carbine and the Sterling submachine gun. However, the British Army was already blessed in its possession of a good squad automatic weapon (the Bren) and these remained apportioned one per squad. They comprised the bulk of the squad’s firepower, even after the introduction of the self-loading rifle (a semi-automatic copy of the Belgian FN-FAL). The British did not deploy a mortar on the squad level. However, there was one 2-inch mortar on the platoon level.

The US Army took a slightly different approach. They believed the experience in Vietnam showed the value of smaller squads carrying a higher proportion of heavier weapons. The traditional 12-man squad armed with semi-automatic rifles and an automatic rifle was knocked down to 9 men: The squad leader carried the M-16 and AN/PRC-6 radio. He commanded two fire teams of four men apiece (each containing one team leader with M-16, grenadier with M-16/203, designated automatic rifleman with M-16 and bipod, and an anti-tank gunner with LAW and M-16). Three squads composed a platoon along with two three-man machinegun teams (team leader with M-16, gunner with M-60 machinegun, and assistant gunner with M-16). The addition of two M-60 machinegun teams created more firepower on the platoon level. The platoon leader could arrange these to give covering fire, using his remaining three squads as his maneuver element. The M-16/203 combination was a particular American creation (along with its M-79 parent). It did not have the range of the Japanese 50 mm mortar. However, it was handier, and could still lay down indirect high-explosive fire, and provide support with both smoke and illumination rounds. The US Army also had 60 mm mortar. This was a bigger, more capable weapon than the Japanese 50 mm weapon. But it was too heavy for use on the squad or even the platoon level. These were only deployed on the company level. The deficiency of the US formation remained the automatic rifleman, a tradition that had gone back to the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) gunner of World War II. The US Army discovered that an automatic rifle was a poor substitute for a real machinegun. A rifle fired in the sustained automatic role easily overheated, and its barrel could not be changed. Post-Vietnam, the US Army adopted the Belgian Minimi to replace the automatic M-16. With an interchangeable barrel and larger magazine, this weapon provided the sustained automatic fire required.

The Republic of Singapore Army, whose experience is 100% in primary and secondary jungle as well as rubber plantation terrain, took the trend one step further. Their squad contained only seven men, but fielded two squad automatic gunners (with 5.56 mm squad automatic weapons), two grenadiers with M-16/203 under slung grenade launchers, and one anti-tank gunner with rocket launcher and assault rifle.

So in short, jungle warfare increased the number of short/sharp engagements on the platoon or even squad level. Platoon and squad leaders had to be more capable of independent action. To do this, each squad (or at least platoon) needed a balanced allocation of weapons that would allow it to complete its mission unaided.

Notes et références

modifierNotes

modifierRéférences

modifier- Moving across a fire zone in a vehicle, especially under armor, dramatically cut casualties.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Weapons and Warfare (London: Phoebus, 1978), Volume 18, p.1929-20, "Molotov Cocktail".

DOCU

modifier

Les tactiques d'infanterie sont la combinaison de concepts militaires et de méthodes de combat utilisées par l'infanterie pour atteindre des objectifs tactiques pendant les opérations militaires.

Les tactiques de l'infanterie varient selon le type d'unité déployé et d'objectif poursuivi. L'infanterie blindée ou motorisée[note 1] est tranportée et/ou appuyée dans l'action par des véhicules, tandis que d'autres peuvent effectuer des opérations amphibies depuis des navires, ou en tant que troupes aéroportées, être « insérées » par parachutages ou planeurs. La tactique utilisée varie aussi en fonction de la nature du terrain d'opération : guerre de position, combat urbain, guerre de jungle, opérations en milieu désertique...

- section 2GM

modifierSince trench warfare had been rendered obsolete by the tank, new infantry tactics were devised. More than ever, battles consisted of infantry working together with tanks, aircraft, artillery, (see combined arms). One example of this is how infantry would be sent ahead of tanks to search for anti-tank teams, while tanks would provide cover for the infantry. Portable radios allowed field commanders to communicate with their HQs, allowing new orders to be relayed instantly.

Another major difference from any other previous conflict was the means of transportation; no longer did soldiers have to walk (or ride a horse) from location to location. The prevalence of motor transport, however, has been overstated; Germany used more horses for transport in WWII than in WWI, and British troops as late as June 1944 were still not fully motorized. Although there were trucks in World War I, their mobility could never be fully exploited because of the trench warfare stalemate, as well as the terribly torn up terrain at the front and the ineffectiveness of vehicles at the time. During World War II, infantry could be moved from one location to another using half-tracks, trucks, and even aircraft, which left them better rested and able to fight once they reached their objective; this also influenced speed of deployment and casualties.[1] A new type of infantry, the paratrooper, was deployed as well. These lightly armed soldiers would parachute behind enemy lines, hoping to catch the enemy off-guard. They were first used by the Germans to seize key bridges in the Netherlands, and prevented their destruction long enough for additional forces to arrive. They required prompt support from regulars, however; First British Airborne was decimated at Arnhem after being left essentially cut off.

To counter the tank threat, WWII infantry initially had few options other than the so-called "Molotov cocktail" (first used by Chinese troops against Japanese tanks around Shanghai in 1937[2]) and anti-tank rifle. Neither was particularly effective, especially if armor was accompanied by supporting infantry. These, and later anti-tank mines, some of which could be magnetically attached to the tank, required the user to get closer than was prudent. Later developments, such as the Bazooka, PIAT, and Panzerfaust, allowed a more effective attack against armor from a distance. Thus, especially in the ruined urban zones, tanks were forced to enter accompanied by squads of infantry.

Marines became prominent during the Pacific War. These soldiers were capable of amphibious warfare on a scale not previously known. As Naval Infantry, both Japanese and American Marines enjoyed the support of naval craft such as battleships, cruisers, and the newly-developed aircraft carriers. As with conventional infantry, the Marines used radios to communicate with their supporting elements. They could call in sea and air bombardment very quickly.

Tactiques d'escouade et de peloton

modifierTactiques offensives

modifierAggressive squad tactics were similar for both sides, though specifics in arms, numbers, and the subtleties of the doctrine differed. The main goal was to advance by means of fire and movement with minimal casualties while maintaining unit effectiveness and control.

The German squad would win the Feuerkampf (fire fight), then occupy key positions. The rifle and machine gun teams were not separate, but part of the Gruppe, though men were often firing at will. Victory went to the side able to concentrate the most fire on target most quickly. Generally, soldiers were ordered to hold fire until the enemy was 600 metres (660 yards) or closer, when troops opened fire on mainly large targets; individuals were fired upon only from 400 meters (440yd) or below.

The German squad had two main formations while moving on the battlefield. When advancing in the Reihe, or single file, formation, the commander took the lead, followed by the machine gunner and his assistants, then riflemen, with the assistant squad commander moving on the rear. The Reihe moved mostly on tracks and it presented a small target on the front. In some cases, the machinegun could be deployed while the rest of the squad held back. In most cases, the soldiers took advantage of the terrain, keeping behind contours and cover, and running out into the open when there were none to be found.

A Reihe could easily be formed into Schützenkette, or skirmish line. The machinegun deployed on the spot, while riflemen came up on the right, left or both sides. The result was a ragged line with men about five paces apart, taking cover whenever available. In areas where resistance was serious, the squad executed "fire and movement". This was used either with the entire squad, or the machinegun team down while riflemen advanced. Commanders were often cautioned not to fire the machinegun until forced to do so by enemy fire. The object of the firefight was to not necessarily to destroy the enemy, but Niederkampfen - to beat down, silence, or neutralize them.

The final phases of an offensive squad action were the fire fight, advance, assault, and occupation of position:

The Fire Fight was the fire unit section. The section commander usually only commanded the light machine gunner (LMG) to open fire upon the enemy. If much cover existed and good fire effect was possible, riflemen took part early. Most riflemen had to be on the front later to prepare for the assault. Usually, they fired individually unless their commander ordered them to focus on one target.

The Advance was the section that worked its way forward in a loose formation. Usually, the LMG formed the front of the attack. The farther the riflemen followed behind the LMG, the more easily the rear machine guns could shoot past them.

The Assault was the main offensive in the squad action. The commander made an assault whenever he was given the opportunity rather than being ordered to do so. The whole section was rushed into the assault while the commander lead the way. Throughout the assault, the enemy had to be engaged with the maximum rate of fire. The LMG took part in the assault, firing on the move. Using hand grenades, machine pistols, rifles, pistols, and entrenching tools, the squad tried to break the enemy resistance. The squad had to reorganize quickly once the assault was over.

When occupying a position (The Occupation of Position), the riflemen group up into twos or threes around the LMG so they could hear the section commander.

The American squad's basic formations were very similar to that of the Germans. The U.S. squad column had the men strung out with the squad leader and BAR man in front with riflemen in a line behind them roughly 60 paces long. This formation was easily controlled and maneuvered and it was suitable for crossing areas open to artillery fire, moving through narrow covered routes, and for fast movement in woods, fog, smoke, and darkness.

The skirmish line was very similar to the Schützenkette formation. In it, the squad was deployed in a line roughly 60 paces long. It was suitable for short rapid dashes but was not easy to control. The squad wedge was an alternative to the skirmish line and was suitable for ready movement in any direction or for emerging from cover. Wedges were often used away from the riflemen's range of fire as it was much more vulnerable than the skirmish line.

In some instances, especially when a squad was working independently to seize an enemy position, the commander ordered the squad to attack in sub-teams. "Team Able", made up of two riflemen scouts, would locate the enemy; "Team Baker", composed of a BAR man and three riflemen, would open fire. "Team Charlie", made up of the squad leader and the last five riflemen, would make the assault. The assault is given whenever possible and without regard to the progress of the other squads. After the assault, the squad advanced, dodging for cover, and the bayonets were fixed. They would move rapidly toward the enemy, firing and advancing in areas occupied by hostile soldiers. Such fire would usually be delivered in a standing position at a rapid rate. After taking the enemy's position, the commander would either order his squad to defend or continue the advance.

The British method formations depended chiefly on the ground and the type of enemy fire that was encountered. Five squad formations were primarily used: blobs, single file, loose file, irregular arrowhead, and the extended line. The blob formation, first used in 1917, referred to ad hoc gatherings of 2 to 4 men, hidden as well as possible. The regular single file formation was only used in certain circumstances, such as when the squad was advancing behind a hedgerow. The loose file formation was a slightly more scattered line suitable for rapid movement, but vulnerable to enemy fire. Arrowheads could deploy rapidly from either flank and were hard to stop from the air. The Extended Line was perfect for the final assault, but it was vulnerable if fired upon from the flank.

The British squad would commonly break up into two groups for the attack. The Bren group consisted of the two-man Bren gun team and second in command that formed one element, while the main body of the riflemen with the squad commander formed another. The larger group that contained the commander was responsible for closing in on the enemy and advancing promptly when under fire. When under effective fire, riflemen went to fully fledged "fire and movement". The riflemen were ordered to fall to the ground as if they had been shot, and then crawl to a good firing position. They took rapid aim and fired independently until the squad commander called for cease fire. On some occasions the Bren group advanced by bounds, to a position where it could effectively commence fire, preferably at 90 degrees to the main assault. In this case both the groups would give each other cover fire. The final attack was made by the riflemen who were ordered to fire at the hip as they went in.

Tactiques défensives

modifierDuring the Second World War, various forms of infantry entrenchments - trenches, ditches, foxholes - were used extensively, sometimes reinforced by anti-tank « dragon's teeth » obstacles .

German defensive squad tactics stressed the importance of integration with larger plans and principles in posts scattered in depth. A Gruppe was expected to dig in at 30 to 40 meters (33-45yd) (the maximum that a squad leader could effectively oversee). Other cover such as single trees and crests were said to attract too much enemy fire and were rarely used. While digging, one member of the squad was to stand sentry. Gaps between dug-in squads may be left, but covered by fire. The placing of the machine gun was key to the German squad defence, which was given several alternative positions, usually being placed 50 meters (55yd) apart.

Pairs of soldiers were deployed in foxholes, trenches, or ditches. The pair stood close together in order to communicate with each other. The small sub-sections would be slightly separated, thus decreasing the effect of enemy fire. If the enemy did not immediately mobilize, the second stage of defense, entrenching, was employed. These trenches were constructed behind the main line where soldiers could be kept back under cover until they were needed.

The defensive firefight was conducted by the machine gun at an effective range while riflemen were concealed in their foxholes until the enemy assault. Enemy grenades falling on the squad's position were avoided by diving away from the blast or by simply throwing or kicking the grenade back. This tactic was very dangerous and U.S. sources report American soldiers losing hands and feet this way.

In the latter part of the war, emphasis was put on defense against armored vehicles. Defensive positions were built on a "tank-proof obstacle" composed of at least one anti-tank weapon as well as artillery support directed by an observer. To intercept enemy tanks probing a defensive position, squads often patrolled with an anti-tank weapon.

Tactiques de choc

modifierTroupes aéroportées

modifierCommandos

modifierKampfgruppe et Combat Command

modifierLa lutte antichar

modifier

Articles connexes

modifierBibliographie

modifier- (en) Dr Steven Bull : World War II Infantry Tactics: Squad and Platoon, 2004 Osprey Ltd.

Notes et références

modifierNotes

modifier- on distingue généralement l'infanterie « blindée/mécanisée » de l'infanterie « motorisée » selon le type d'engins utilisés : l'infanterie blindée/mécanisée se déplace et combat à bord d'engins du type semi-chenillé ou Véhicule de combat d'infanterie - Sdkfz 251 - l'infanterie « motorisée » se déplaçant en camions et véhicules légers non-blindés.

Références

modifier- Moving across a fire zone in a vehicle, especially under armor, dramatically cut casualties.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Weapons and Warfare (London: Phoebus, 1978), Volume 18, p.1929-20, "Molotov Cocktail".

Article - section Jungle warfare

modifierJungle warfare was heavily shaped by the experiences of all the major powers in the Southeast Asian theater of operations during the Second World War.

Jungle terrain tended to break up and isolate units. It tended to fragment the battle. It called for greater independence and leadership among junior leaders, and all the major powers increased the level of training and experience level required for junior officers and NCOs.

But fights in which squad or platoon leaders found themselves fighting on their own also called for more firepower.

All the combatants, therefore, found ways to increase both the firepower of individual squads and platoons. The intent was to ensure that they could fight on their own … which often proved to be the case.

Japan, as one example, increased the number of heavy weapons in each squad. The "strengthened" squad used from 1942 onwards was normally 15 men. The Japanese squad contained one squad automatic weapon (a machinegun fed from a magazine and light enough to be carried by one gunner and an assistant ammunition bearer). The squad's TO&E also included a grenade launcher team armed with what historians often mistakenly call a "knee mortar". This was in fact a light mortar of 50mm that threw high explosive, illumination and smoke rounds out to as much as 400 meters. Set on the ground and fired with arm outstretched, the operator varied the range by adjusting the height of the firing pin within the barrel (allowing the mortar to be fired through small holes in the jungle canopy). A designated sniper was also part of the team, as was a grenadier with a rifle-grenade launcher. The balance of the squad carried bolt-action rifles. The result was that each squad was now a self-sufficient combat unit. Each squad had an automatic weapons capability. In a defensive role, the machinegun could be set to create a “beaten zone” of bullets through which no enemy could advance and survive. In an attack, it could throw out a hail of bullets to keep the opponent’s head down while friendly troops advanced. The light mortar gave the squad leader an indirect "hip-pocket artillery" capability. It could fire high-explosive and fragmentation rounds to flush enemy out of dugouts and hides. It could fire smoke to conceal an advance, or illumination rounds to light up any enemy target at night. The sniper gave the squad leader a long-range point-target-killing capability. Four squads composed a platoon. There was no headquarters section, only the platoon leader and the platoon sergeant. In effect, the platoon could fight as four independent, self-contained battle units (a concept very similar to the US Ranger “chalks.”)

The British Army did extensive fighting in the jungles and rubber plantations of Malaya during the Emergency, and in Borneo against Indonesia during the Confrontation. As a result of these experiences, the British increased the close-range firepower of their individual riflemen by replacing the pre-World War II bolt-action Lee-Enfield with lighter, automatic weapons like the American M-2 carbine and the Sterling submachine gun. However, the British Army was already blessed in its possession of a good squad automatic weapon (the Bren) and these remained apportioned one per squad. They comprised the bulk of the squad’s firepower, even after the introduction of the self-loading rifle (a semi-automatic copy of the Belgian FN-FAL). The British did not deploy a mortar on the squad level. However, there was one 2-inch mortar on the platoon level.

The US Army took a slightly different approach. They believed the experience in Vietnam showed the value of smaller squads carrying a higher proportion of heavier weapons. The traditional 12-man squad armed with semi-automatic rifles and an automatic rifle was knocked down to 9 men: The squad leader carried the M-16 and AN/PRC-6 radio. He commanded two fire teams of four men apiece (each containing one team leader with M-16, grenadier with M-16/203, designated automatic rifleman with M-16 and bipod, and an anti-tank gunner with LAW and M-16). Three squads composed a platoon along with two three-man machinegun teams (team leader with M-16, gunner with M-60 machinegun, and assistant gunner with M-16). The addition of two M-60 machinegun teams created more firepower on the platoon level. The platoon leader could arrange these to give covering fire, using his remaining three squads as his maneuver element. The M-16/203 combination was a particular American creation (along with its M-79 parent). It did not have the range of the Japanese 50 mm mortar. However, it was handier, and could still lay down indirect high-explosive fire, and provide support with both smoke and illumination rounds. The US Army also had 60 mm mortar. This was a bigger, more capable weapon than the Japanese 50 mm weapon. But it was too heavy for use on the squad or even the platoon level. These were only deployed on the company level. The deficiency of the US formation remained the automatic rifleman, a tradition that had gone back to the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) gunner of World War II. The US Army discovered that an automatic rifle was a poor substitute for a real machinegun. A rifle fired in the sustained automatic role easily overheated, and its barrel could not be changed. Post-Vietnam, the US Army adopted the Belgian Minimi to replace the automatic M-16. With an interchangeable barrel and larger magazine, this weapon provided the sustained automatic fire required.

The Republic of Singapore Army, whose experience is 100% in primary and secondary jungle as well as rubber plantation terrain, took the trend one step further. Their squad contained only seven men, but fielded two squad automatic gunners (with 5.56 mm squad automatic weapons), two grenadiers with M-16/203 under slung grenade launchers, and one anti-tank gunner with rocket launcher and assault rifle.

So in short, jungle warfare increased the number of short/sharp engagements on the platoon or even squad level. Platoon and squad leaders had to be more capable of independent action. To do this, each squad (or at least platoon) needed a balanced allocation of weapons that would allow it to complete its mission unaided.

Articles connexes

modifier- Centre d'instruction de la guerre dans la jungle

- Centre d'entraînement commando en forêt équatoriale du Gabon

- Centre d'entraînement à la forêt équatoriale